Damage mechanics

Damage calculation

Aviation

The game's engine simulates every bullet that is fired for over 2 km before they are deleted, with exceptions for bigger shells such as those fired by the 50 mm BK 5 or 57 mm Molins cannons. The different shells also have different effects on module damage. More of these shell effects can be read in the Ammunition section. Every aircraft has its skin airfoil and material modeled, too. It is therefore possible to see a tracer shell ricochet off an enemy plane's duralumin skin. Some aircraft are quite well armoured from certain angles. For example, the TB-3 is constructed mainly with 3 mm of corrugated steel. The IL-2 and IL-10 series of Russian attackers are also quite durable.

Naval targets in air battles have their own damage mechanics modeled. See this page for more detail.

Ground forces: Penetration

Line of sight thickness

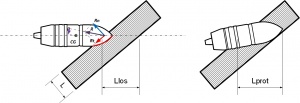

Llos = L / cos@

- Llos = Length line of sight (Line of sight thickness) - L = armour plate thickness - @ = angle of armour

Normalization

The calculation of the armour piercing effect of projectiles on sloped armour:

Before the "Weapons of Victory" update, the armour-piercing effect calculation of an angled hit was made based on the normal principle for most tank-based games via normal line of sight thickness, as seen in the picture above.

At the same time (still before "Weapons of Victory"), for different types of shells a certain distortion of the angle of attack was taken into account depending on the type of projectile (sharp or blunt-nosed shell) and the ratio between the calibre of the projectile to the armour thickness normal (perpendicular vector). In blunt-nosed shells, the final angle which were used for calculation of the armour thickness was reduced, and in sharp-nosed shells - slightly increased, i.e. a normalization factor was artificially added after the crude line of sight thickness calculation.

However, despite the fact that this method is good enough in most cases - the calculation results do not always completely agree with the actual results of tank armour penetration tests. This was particularly noticeable in cases of penetration with high angles of approach.

There are several forces applied to a real shell at the moment of impact with any armour. These forces will bend the trajectory of a projectile which is entering any armour depending on the shape of the projectile nose, the angle of attack, the relation between the calibre of the projectile and the armour thickness normal/sharp-nosed shells while hitting the armour, receive resistance in the form of a larger normal reaction “Rn” and smaller tangential reaction “Rt”. The resultant of these forces relative to the centre of inertia of a projectile creates a moment that de-normalizes the shell, which in turn increases its course through the armour.

Blunt-nosed shells, when hitting an obstacle with its “blunted” tip, will form a ledge in the armour, and will gain from the obstacle and ledge a greater tangential and lesser normal reactions. The moment of the resultant will angle-in the shell towards the normal and as a result it reduces the path of the projectile inside the armour.The larger is the elongation (length-to-diameter ratio) of the projectile - the stronger is the normalization effect of the projectile. Modern APFSDS munitions have a greater elongation and during an angled hit often penetrate thicker armour than the equivalent of a plate normal.

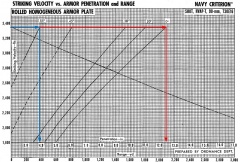

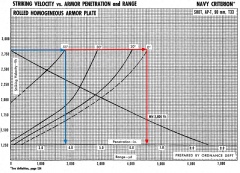

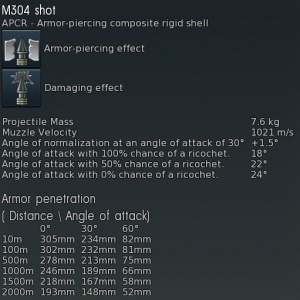

However, the projectiles that are modeled in our game were fairly short ones and at high angles of attack had a large de-normalizing effect - both sharp-nosed (for which this effect was bigger), and blunt-nosed (with a smaller effect). The APCR shells of the time had the maximum effect. Thus for the American 90 mm APCR prototype M304 shell (Terminal ballistic Data Vol 3 p.157) as we can see the penetration value at an angle of attack of 55 degrees is more than 3 times less than penetration by normal (see Pic.4). If at an angle of 0 degrees of attack, the projectile could penetrate a little more than 12 inches of armour (305 mm), an angle of approach of 55 degrees makes the shell penetrate a little less than four inches (101.6 mm); Picture 1. Which is comparable with penetration values of the T33 calibre sharp-nosed shell; Picture 2

Picture 1:

M304 APCR prototype of the M26 Pershing

These graphs also display that for the calibre shell the drop of penetration from angle of attack is not as huge as for the APCR.

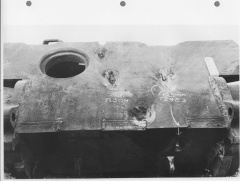

In “Pic.6” you can see a photo which shows a strong drop of penetration values for APCR projectiles at high angles of attack. This test was based on the shooting of the frontal part of the Tiger 2 tank. As can be seen, both APCR projectiles - 90 mm and 105 mm, did not penetrate the upper side of the tank plate, but they broke through the lower one which has a smaller thickness.

This effect has been reproduced in the game since update "1.49". For each type of projectile, and for different ratios of calibre/barrier thickness at different angles of attack - own armour penetration fall ratios. Most of the data is taken from the publications “WWII Ballistics: Armor and Gunnery” and “Terminal ballistic Data Vol 2 and 3.”.

Tooltips show this as well for each shell, they display the penetration of the shells at three different angles of attack. Arcade penetration indicator accounts for this effect. It also takes into account not only the first part of the tank armour, but several parts under it as well, which will give a more accurate indication of the penetration with such complex structures as gun mantlets and shielded armour.

Breach / Overmatch / Stamping

Overmatching occurs if a shell hits sloped armour that is thinner then the calibre of the tank shell. Overmatching basically neglects the sloped armour ricochet effect. This mechanic was added to the game with Update 1.63 "Desert Hunters" and applies to shells 1.3x bigger in diameter than the armour thickness to have a reduced sloping effect.

The bigger the shell, the more effective overmatch is. Shells with sufficient penetration that are greater than 7 x bigger in diameter than the armour thickness will ignore ricochet chance and angle of attack, acting as if the shell is impacting a flat plate.

As of 1.85.0.121 a simple formula to calculate minimum shell calibre required to achieve maximum overmatching is this:

Minimum shell calibre > Armour thickness * 7.0

This mechanic requires a shell with penetration greater than the nominal thickness of the impacted armour plate. Shells without sufficient penetration will never penetrate, no matter the calibre.

Hull-break

| This mechanic is no longer in use in ground battles and has been replaced by overpressure. However, hullbreak remains active in naval battles for coastal ships. |

In Update 1.65 "Way of the Samurai", the hull-break mechanic was added into the game for thin-hulled vehicles. This generally applies to non-armoured and lightly-armoured vehicles (with up to 25 mm thickness of hull armour). Unlike the usual method of incapacitating the crew members of a vehicle to secure a destruction, the hull-break mechanics implements a hull and module based damage system to destroy these vehicles.

The initial version set the criteria as "on the kinetic impact, hits with penetration of the shell of 150 mm calibre on any part of the hull or turret (inclusive of the breech). Or even hitting following penetration of few structural elements of shells of small calibre, upwards of 75 mm and higher. For HE shells, impacts by 75-76 mm HE shells to the hull or turret will be effective. For large calibre HE shells (122-152 mm) hits to chassis components will be counted as fatal."

In Update 1.71 "New E.R.A", the hull-break mechanics was refined towards kinetic shells as requiring the "need to directly hit them with a shell of high energy (more than 1.4 MJ) on one of the major internal modules. E.g. engine, transmission, breech or shell storage." In Update "Ixwa Strike", the hull-break mechanic was removed entirely from ground battles, in favour of the more advanced and realistic overpressure mechanic.

Overpressure

In Update "Ixwa Strike", the "overpressure" mechanic was introduced, replacing the hull-break mechanic. It simulates the extreme pressures formed by the shockwave of an HE-based shell explosion, and their effect on the crew inside the vehicle. Overpressure damage calculations are run when the crew is exposed to the overpressure wave.

For open-topped vehicles, this happens whenever the vehicle is within the fragment dispersion radius of the shell's explosion. This makes them extremely vulnerable to any explosive damage.

For closed-up vehicles, this happens when explosion effect manages to penetrate the armour of the vehicle:

For HE, overpressure damage is calculated when a shell fragment from an explosion hits something inside of the vehicle, proving that explosion got inside of it. This leads to high-yield explosives nearly always taking out a vehicle in a single hit, due to the shockwave being able to move around frontal armour and to hit the entirety of the crew that way.

HEAT and HESH shells and ATGM can also create overpressure damage but are less effective at it compared to HE ammunition and seem to only affect vehicles when very thin parts of the hull or their critical weak spots are hit directly, with overall armour thickness of hit surface having to be below 15 mm RHA, since their explosive power is directed towards creating special effects (molten jet for HEAT and scabbing for HESH) instead of producing shockwaves. There are exceptions in HEAT ammunition, which can deal overpressure damage through 20 mm (select few powerful HEAT ATGM) or 30 mm RHA (most tandem missiles). Tanks with reasonable amount of armour will not take overpressure damage from HEAT, even if special effect penetrates them easily.

This mechanic affects vehicles with thin armour negatively, but, unlike with the hullbreak, any tank is potentially vulnerable to overpressure damage. As a result, it makes not only light, but also heavy tanks easier to destroy by using bombs, rockets, big HE shells or artillery strikes. To utilize the mechanic effectively, be sure to aim for a weak spots on the armour, such as roofs, vents, bellies, tank rear and overtrack sponsons, to maximize the chance of a successful penetration.

Overpressure damage can be reduced or negated by tanks with compartment separators (internal RHA screens, engine compartment being used as a shield, etc.), meaning only the crew in hit part of the tank will take damage.

Creating digital weaponry

The following is an exclusive essay by the Gaijin development team to explain how guns' real life behaviour is translated into the game. Hence the focus is primarily on the ground forces part of War Thunder. Also the tone of the text is more personal than usual on the WT Wikipedia.

Weapon

We really love the variety of the military technology from various countries, and we always try to tune its behavior to get it as close to the real-life version as possible. For this reason, we have to pay attention to tuning weapons as well – this is the only way we can show and give emphasis to the entire scope of variety in military vehicles, in addition to showcasing their firepower. Each weapon is unique in its own way, and in order to reproduce this uniqueness, we study a mass of documentation and scrupulously tune not only the weapons, but even each separate ammunition type for each of them. This approach allows us to convey the spirit of each military vehicle in our game as precisely as we can.

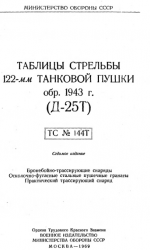

First we will tell you how we tune machine guns and cannons. Aircraft and tank weapons work on similar principles, so for the sake of this example, we'll just take one – the 122 mm D-25T cannon, which was installed on the tanks like the IS-2, IS-3 and the IS-4M. Using this weapon's tuning as an example, we'll show you how all the other weapons in the game are tuned and how they work.

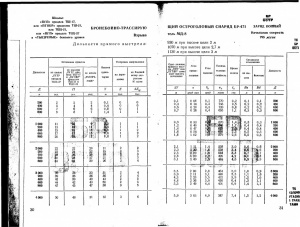

The weapon parameters include such variables as its spread and the technical upper limit for its rate of fire. While tuning the weaponry, just like when we tune the shells, we use different documentation like field tests and technical documentation for the vehicles themselves. The search for correct documentation is one of the most difficult and slow processes because different sources show different and often conflicting data. Sometimes it takes time to verify the source, since we have to do reseaech of all the data available. Here we are using data from “aiming data chart of 122mm tank cannon of 1943 variant D-25T” Army publishing MO USSR Moscow, 1969, as well as “Ammunition for 122mm cannons for ground, tank and self propelled artillery. Instruction” War ministry of USSR 1952, “Artillery sergeant textbook” book one, war publishing of NKO 1944.

At the moment, the rate of fire in our game is an averaged value, since in real life, reload time depends on a multitude of variables. Among other things, these variables include how the ammunition is stored (when expending ammunition, this forces the loader to get shells from a less convenient place in the vehicle) and the weight and shape of the shells (for example, heavy and bulky shells get harder to reload over a longer period of time). We have plans to simulate reloading with such mechanics taken into account, which means introducing a variable rate of fire depending on the state of the ammunition, the loader's fatigue, and the position of the turret itself, which defines which ammunition stowage area is closer and which farther away. For example, the Patton houses just a small part of its ammunition right next to the gunner – the rest is in stowage areas located in a floor-level section, which take a lot longer to access. If we introduce such a system, this will mean that the first rounds will be loaded much more quickly than the current reload time, and later rounds will take much longer. This system is still only in development, however.

Rate of fire is displayed in terms of shots per second, and our weapon has a value of 0.048 shots per second, or 1 shot every 20.8 seconds. This is the minimal reload time for any round for this vehicle with maxed out crew skills.

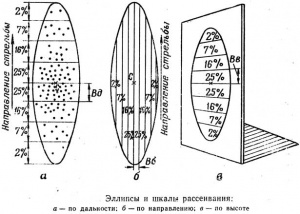

The spread is calculated in the following way: From the firing tables we know the circular error probability (CEP) of the shot for both (horizontal and vertical) deviation axes at a distance of 1,000 m. For example, the given cannon has a CEP equal to 0.3 m, so we can calculate the angle of dispersion for the weapon. As half of both axes of dispersion are equal to four CEP for either the vertical or horizontal, it equals 1.2 m in our case, which is 0.069 degrees on both the vertical and horizontal. That means that at 1,000 m, the D-25T's maximum spread will amount to roughly 2.4 m, which means that even at maximum spread, you will still hit the tank's silhouette even at that distance. Many weapons, of course, will have different mean average deviation values for horizontal and vertical and then the spread will appear to be ellipse shaped. At the same time, in half of the cases, the shell will hit at half distance from the edges closer to the center than at the maximum level of angular displacement. This is how we simulate the level of weapon accuracy comparable to the reality of real combat vehicles.

Shells

Now that the weapon has its primary characteristics and is ready for battle, we move on to tuning its ammunition. A great many forms of ammunition were used, and listing them all along with describing how they work is a subject for a separate and long treatise. To show the adjustments we make, we'll use one of the shells for our weapon as an example – a pointed armour-piercing high-explosive round.

First of all, we set such parameters as the shell's weight (25 kg), its calibre (0.122 m), its muzzle velocity (795 m/s), and its type (armour-piercing high-explosive – APHE). These values determine the round's ricochet and normalization, the basic kinetic damage parameters, and the round's additional properties, such as the presence of explosive material. Next we have its ballistic settings (the round's energy loss), and the chance that the round will cause a fire when it hits a fire-vulnerable module – this setting is separate from the explosive setting, and we can use it to simulate the chance of ignition from tracers (if tracer ammunition is used) or ignition from sparks produced when a round hits an obstacle.

In addition, there are settings like the round's fragmenting action, the detonator parameters and the power of the explosion itself. The explosive wave and the shrapnel broadly take into account both the shape of the landscape and any obstacles in their path (in the real world, explosives don't disperse in a straight line or from a single point). This means that a tank can hide from shockwaves and shrapnel behind various obstacles, and separate modules on a tank will protect the other modules from taking additional damage. For example, a round which penetrates the rear armour of a tank and explodes behind the engine might do no harm to the crew, as the engine blocks the shrapnel and the shockwave.

Each individual shell in our physics model has its own settings, such as the explosive power, i.e. the thickness its shockwave can penetrate at short range, and the explosion radius at which its power is maximum and at which it fully disappears. Apart from the explosion itself, the shell also has a fragmenting action which we provide as a radius, shrapnel amount and shrapnel penetration. It's also worth noting that secondary shrapnel is also added to shell shrapnel. Secondary shrapnel occurs after the target itself is penetrated.

As you can see, there are quite a few of these settings, and we consider them a very important part of allowing players to determine the required effect of a shell without reading a long list of its characteristics. This is precisely why the shell icons are different depending on their parameters. If the round has high penetration, then its icon will show exactly that. If it has an explosive substance and/or a fragmenting effect from the shell itself, this will also be added to the icon. Be careful when selecting a shell – the various shells don't just have different penetration characteristics and fragmenting actions or explosive properties, they also lose their energy differently. Note how the numerical value of armour penetration changes depending on the distance of the shot. This is shown on the shell's tooltip.

When considering the damage model, it is very important to at least point out the fact that in our game, we model the characteristics of various types of materials – glass, reinforced glass, wood and various types of metal used in both aircraft and ground vehicles. Each material has its own equivalent durability in terms of armour steel thickness. For example, we calculate that 100 mm rolled armour has an armour steel thickness equivalent to 100 mm, cast armour has a 94 mm equivalent thickness, reinforced glass – 20 mm and wood – 10 mm.

Netcode or Defining the impact point

One of the most important questions, especially in online games, is the question of defining the impact point on an enemy when two players may have internet connections with entirely different levels of quality. This is particularly relevant in a game in which the combatants can move at high speed – in our case, in air battles.

For our game, we developed a system to define the position of each player independent of the delay they're playing with. We won't get into all the little details, but in short, this works in the following manner: the server receives only the players' own control commands (for example: joystick movement, trigger press, flap controls and so on) and their individual actions (such as activating fire extinguishers and respawn requests) and using this information, it calculates the movement and actions of each player. At the same time, it separately calculates each shell fired, including their full ballistics, including the difference between vehicle speeds (a shell will do more damage in head-on attack for the two aircraft than it would to aircraft flying away) and all the effects these shells have – all of this is independent of the vehicle's rate of fire – without any simplification! For example, the Hurricane's machine guns have a rate of fire of 1,000 shots per minute, which means that when you pull the trigger on the Hurricane Mk II, which has 12 machine guns, this aircraft alone fires 200 bullets per second into the air, each of them has their flight and trajectory individually calculated by the server! We will remind you about how damage calculation works inside the game for both aviation and ground vehicles after a hit:

- Breach check - if calibre is six times higher than plate thickness it breaches the plate automatically.

- If there is no breach - bound check.

- If there is no bound shot - then we do a penetration check, for which the following characteristics are taken into account - current penetration value, armour slope angle, and slope angle of the machine itself, angle of impact. Armour thickness is calculated and we do a check as to whether a shell can or cannot penetrate the armour. If not and the shell has explosives - it detonates and attachments can be damaged.

- If there is penetration the shell deals the damage to the armour, loses penetration value and kinetic damage proportionally to armour thickness and goes further. Also each kinetic shell creates a shard cone that can damage modules and crew in the sector.

- The shell itself goes further and when hitting any internal module all the above mentioned checks are made (excluding cases when a fragmentation shell hits armour with thickness thinner than 3-4mm - it will not generate a fragmentation cone then). Checks are made until the penetration value of a shell is enough to penetrate a module or until the fuse goes off (if the shell has explosives and armour was not thick enough to make it go off) A distance needed for the fuse is 0.5-1.5 m from the penetration point depending on calibre and type.

- When the fuse goes off the explosion follows which creates HE and fragmentary spheres of damage. Crew members and modules within the spheres may be damaged by shards and shockwave.

The server then sends the results of these calculations to each player in the session to synchronize the data, which is also calculated on the players' own systems.

Thanks to lag compensation, which consists of physical extrapolation, visual model display interpolation and time rewind with extra physical simulation, you always see the surrounding players in positions as close as possible to their real positions, which allows players to lead their opponents and target critical areas on their target regardless of the ping of any of the battle's participants (up to a certain point, of course). Any physical objects in the world, particularly heavy vehicles, possess inertia and physical properties that significantly constrict their "cone of uncertainty" – their possible states in space over a time delay – which provides a means to achieve significantly better lag compensation results than usually possible in online shooters. It also allows for creating a response in the game entirely independent of the server's reciprocal response, which means that all your actions (such as shooting and manoeuvring) are applied in your client immediately and without delay. We try, as much as it is possible to do so, to ensure that delay in contacting the server does not stop players from enjoying the game, and thanks to this system, players with various levels of ping on various servers will barely notice the difference in gameplay. Only when players have extremely high ping will they see their opponents' sharp manoeuvres far later and sharper than when they actually happened.

Of course, no algorithm can make up for an unstable connection, when network packets don't reach the client or the server. In such cases, players may see their opponents' manoeuvres with a delay or distortion, and may even experience other problems in the game – it all depends on how often the packets drop. However, here too we have created special mechanisms to help ensure that such problems affect the players as little as possible. For example, the main movement and firing controls can suffer a packet loss of over 50%. This allows us to even further reduce the consequences of poor connections. However, it's worth remembering than any multiplayer game will be better if you have a good internet connection!

Media

- Videos