Difference between revisions of "AIM-9C Sidewinder"

(Added missiles) (Tag: Visual edit) |

(→Comparison with analogues: add table from template) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

The AIM-9C is superior to its most immediate Soviet counterpart, the R-3R, having better speed, overload, range, as well as guidance time. It only falls behind in terms of raw explosive power, due to the R-3R's payload of 8.8 kg TNT equivalent. | The AIM-9C is superior to its most immediate Soviet counterpart, the R-3R, having better speed, overload, range, as well as guidance time. It only falls behind in terms of raw explosive power, due to the R-3R's payload of 8.8 kg TNT equivalent. | ||

| − | The AIM-9C is the second SARH AAM available in the US air tree, the first one being the somewhat lacklustre [[AIM-7C Sparrow]] available on the [[F3H-2|F3H-2 Demon]]. Although capable of Mach 3 speeds, and housing a deadly 11.5 kg TNT equivalent payload, | + | The AIM-9C is the second SARH AAM available in the US air tree, the first one being the somewhat lacklustre [[AIM-7C Sparrow]] available on the [[F3H-2|F3H-2 Demon]]. Although capable of Mach 3 speeds, and housing a deadly 11.5 kg TNT equivalent payload, the AIM-7C suffers from a low maximum overload for such a big missile (only 15G), and only having a third of the AIM-9C's guidance time (20s vs 60s). |

| + | |||

| + | {{AIM-9 Comparison Table}} | ||

== Usage in battles == | == Usage in battles == | ||

| Line 74: | Line 76: | ||

===Development=== | ===Development=== | ||

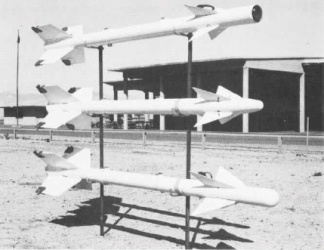

[[File:AIM-9B-9D-9C NAN3-71.jpg|x250px|right|thumb|none|A rack of Sidewinder missiles used by the US Navy. From top to bottom: [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|AIM-9B]], [[AIM-9D Sidewinder|AIM-9D]], and [[AIM-9C Sidewinder|AIM-9C]].]] | [[File:AIM-9B-9D-9C NAN3-71.jpg|x250px|right|thumb|none|A rack of Sidewinder missiles used by the US Navy. From top to bottom: [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|AIM-9B]], [[AIM-9D Sidewinder|AIM-9D]], and [[AIM-9C Sidewinder|AIM-9C]].]] | ||

| − | Limitations in the initial Sidewinder model, the ''AAM-N-7 Sidewinder IA'' (later designated in 1963 the [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|AIM-9B]]), caused the United States Navy to begin developing the next generation of Sidewinders at China Lake. The goal was to improve the missile's envelope, as the Sidewinder's restricted turning ability meant that aware pilots can easily turn and evade the incoming missile. Development on this new Sidewinder missile soon split into two separate project for different seeker heads, one with an infrared alternative head (IRAH) as the ''Sidewinder 1C Mod 29'', which would become the [[AIM-9D Sidewinder|AIM-9D]], and the other with a semi-active radar alternative head (SARAH) as the ''Sidewinder 1C Mod 30'', which would become the [[AIM-9C Sidewinder|AIM-9C]].<ref name="Westrum_ChinaLakeAIM9_2ndGen">Westrum 2013, p.176</ref> A | + | Limitations in the initial Sidewinder model, the ''AAM-N-7 Sidewinder IA'' (later designated in 1963 the [[AIM-9B Sidewinder|AIM-9B]]), caused the United States Navy to begin developing the next generation of Sidewinders at China Lake. The goal was to improve the missile's envelope, as the Sidewinder's restricted turning ability meant that aware pilots can easily turn and evade the incoming missile. Development on this new Sidewinder missile soon split into two separate project for different seeker heads, one with an infrared alternative head (IRAH) as the ''Sidewinder 1C Mod 29'', which would become the [[AIM-9D Sidewinder|AIM-9D]], and the other with a semi-active radar alternative head (SARAH) as the ''Sidewinder 1C Mod 30'', which would become the [[AIM-9C Sidewinder|AIM-9C]].<ref name="Westrum_ChinaLakeAIM9_2ndGen">Westrum 2013, p.176</ref> A SARH guidance system was useful in that it would allow a Sidewinder to perform an all-aspect attack with radar, and was all-weather, not interfered by the environmental factors like a IR seeker was.<ref name="Westrum_ChinaLakeAIM9_AIM9C">Westrum 2013, p.182-184</ref> |

The AIM-9C shared the same missile improvements as the AIM-9D, namely a Hercules MK 36 solid-fuel rocket motor that allowed the missile to go faster and as far as 18 km, large fins for control, and a MK 48 continuous-rod warhead for increased lethality.<ref name="Designation_Sidewinder">Parsch 2008</ref> | The AIM-9C shared the same missile improvements as the AIM-9D, namely a Hercules MK 36 solid-fuel rocket motor that allowed the missile to go faster and as far as 18 km, large fins for control, and a MK 48 continuous-rod warhead for increased lethality.<ref name="Designation_Sidewinder">Parsch 2008</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:48, 22 October 2024

| This page is about the American air-to-air missile AIM-9C Sidewinder. For other versions, see AIM-9 Sidewinder (Family). |

Contents

Description

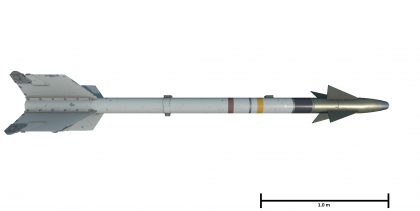

The AIM-9C Sidewinder is an American semi-active radar-homing air-to-air missile. It was introduced in Update "Direct Hit".

Vehicles equipped with this weapon

General info

| Missile characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Mass | 95 kg |

| Guidance | SARH |

| Signal | Pulse |

| Lock range | 9 km |

| Launch range | 18 km |

| Maximum speed | 2.5 M |

| Maximum overload | 18 G |

| Missile guidance time | 60 secs |

| Explosive mass | 4.69 kg TNTeq |

Effective damage

The AIM-9C boasts identical explosive charge as its infrared-guided brother, the AIM-9D, that being 2.95 kg of HMX, equivalent to 4.69 kg of TNT. It's enough to destroy an air target in one hit, or at the very least, to severely damage it.

Comparison with analogues

The AIM-9C is superior to its most immediate Soviet counterpart, the R-3R, having better speed, overload, range, as well as guidance time. It only falls behind in terms of raw explosive power, due to the R-3R's payload of 8.8 kg TNT equivalent.

The AIM-9C is the second SARH AAM available in the US air tree, the first one being the somewhat lacklustre AIM-7C Sparrow available on the F3H-2 Demon. Although capable of Mach 3 speeds, and housing a deadly 11.5 kg TNT equivalent payload, the AIM-7C suffers from a low maximum overload for such a big missile (only 15G), and only having a third of the AIM-9C's guidance time (20s vs 60s).

- AIM-9B FGW.2 Sidewinder - A European-licensed version of the AIM-9B with their own improvements; however the performance in-game are quite similar.

- R-3S/PL-2 - Infamous as a reverse-engineered variant of the AIM-9B, the R-3 missile shares many of its in-game performances with the AIM-9B, only falling slightly short in locking and launching range.

- Shafrir - Shares in-game performance values despite their design differences

- Rb24 - Licensed-produced version of the AIM-9B for the Swedish, and as such shares in-game performance values.

| Missile | Guidance | Lock range (rear-aspect)(km) |

Launch range (km) |

Maximum speed (Mach) |

Maximum overload (g) |

Mass (kg) |

TNT Equivalent (kg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Aspect | Time | Uncaged seeker | Radar slaving | ||||||||

| |

AIM-9B Sidewinder | IR | Rear | 20 | |

|

4 | 10 | 1.7 | 10 | 72 | 7.62 |

| |

AIM-9C Sidewinder | SARH | Front | 60 | |

|

9 | 18 | 2.5 | 18 | 95 | 4.69 |

| |

AIM-9D Sidewinder[note 1] | IR | Rear | 20 | |

|

5.5 | 18 | 2.5 | 18 | 88 | 4.69 |

| |

AIM-9E Sidewinder[note 2] | IR | Rear | 20 | |

|

5.5 | 18 | 2.8 | 10 | 76 | 7.62 |

| |

AIM-9G Sidewinder | IR | Rear | 60 | |

|

5.5 | 18 | 2.5 | 18 | 88 | 3.53 |

| |

AIM-9H Sidewinder | IR | Rear | 60 | |

|

5.5 | 18 | 2.5 | 18 | 88 | 3.53 |

| |

AIM-9J Sidewinder[note 3] | IR | Rear | 40 | |

|

5.5 | 18 | 2.5 | 20 | 76 | 7.62 |

| |

AIM-9L Sidewinder | IR | All | 60 | |

|

11 | 18 | 2.5 | 30 | 84 | 4.58 |

| |

AIM-9M Sidewinder | IR | All | 60 | |

|

11 | 18 | 2.5 | 30 | 84 | 4.58 |

| |

AIM-9P Sidewinder | IR | Rear | 40 | |

|

5.5 | 18 | 2.5 | 20 | 76.93 | 7.62 |

| |

AIM-9P4 Sidewinder | IR | All | 40 | |

|

11 | 18 | 2.5 | 20 | 76.93 | 7.62 |

| |

AIM-9B FGW.2 Sidewinder | IR | Rear | 20 | |

|

5.5 | 10 | 1.7 | 10 | 72 | 7.62 |

| |

Shafrir | IR | Rear | 20 | |

|

7 | 10 | 1.7 | 11 | 65 | 7.62 |

| |

RB24 | IR | Rear | 20 | |

|

4 | 10 | 1.7 | 10 | 72 | 7.62 |

| |

R-3S | IR | Rear | 21 | |

|

9 | 10 | 1.7 | 10 | 75 | 8.8 |

| |

PL-2 | IR | Rear | 21 | |

|

9 | 10 | 1.7 | 10 | 75 | 8.8 |

Usage in battles

The AIM-9C can be handily used in head-on situations, due to it being a SARH missile, albeit due to the F-8E's radar lacking a nose-centred BVR search mode, acquiring a radar lock in time can be tricky, along with its susceptibility to chaff, making reliable hits difficult. It's best used on unaware opponents, or on those who have already exhausted their countermeasures in previous engagements. However, if radar lock on target is successfully re-acquired after losing it (due to chaff or other factors) the missile will immediately begin to track the target again, which along with its good manoeuvrability, gives it decent chances of a successful shootdown in dogfights as well.

Pros and cons

Pros:

- Being a semi-active radar homing (SARH) missile, it has all-aspect ability and is immune to flares

- Begins turning almost immediately after launch, compared to AIM-7 Sparrows and its variants which travel in a straight line for a short amount of time before tracking

- Has the good range of the AIM-9D (3 km range from rear aspect), along with a long burn time

Cons:

- Being a SARH missile, its usefulness is limited on low-altitude targets due to ground clutter

- Requires constant radar lock; a single chaff burst will likely defeat the missile

- Outcome somewhat unreliable due to chaff susceptibility

- Tends to lose lock when the target turns in a direction, then quickly turns the opposite way

History

Development

Limitations in the initial Sidewinder model, the AAM-N-7 Sidewinder IA (later designated in 1963 the AIM-9B), caused the United States Navy to begin developing the next generation of Sidewinders at China Lake. The goal was to improve the missile's envelope, as the Sidewinder's restricted turning ability meant that aware pilots can easily turn and evade the incoming missile. Development on this new Sidewinder missile soon split into two separate project for different seeker heads, one with an infrared alternative head (IRAH) as the Sidewinder 1C Mod 29, which would become the AIM-9D, and the other with a semi-active radar alternative head (SARAH) as the Sidewinder 1C Mod 30, which would become the AIM-9C.[1] A SARH guidance system was useful in that it would allow a Sidewinder to perform an all-aspect attack with radar, and was all-weather, not interfered by the environmental factors like a IR seeker was.[2]

The AIM-9C shared the same missile improvements as the AIM-9D, namely a Hercules MK 36 solid-fuel rocket motor that allowed the missile to go faster and as far as 18 km, large fins for control, and a MK 48 continuous-rod warhead for increased lethality.[3]

Starting development in 1957 under Thomas S. Amlie, the AIM-9C's intent was to provide a fleet-defense weapon for aircraft on the World War II-era Essex-class carriers, which carried the F-8 Crusader aircraft that could not carry the larger AIM-7 Sparrow SARAH missiles. Developing a working radar seeker was difficult, with the development team reviewing the technical reports of the AIM-4A Falcon to fix some issues. However, another issue with the AIM-9C's development is finding a suitable radar that could use it, as the AIM-9C called for the use of a 24-inch diameter radar while the Crusader used a 13-inch diameter radar. This would eventually be resolved with the Crusaders integrating a AN/APQ-83 radar. The AIM-9C went through operational evaluation with the US Navy in 1964, alongside the AIM-9D, and the AIM-9C demonstrated a 77% single-shot kill probability. Two F-8 squadron based in NAS Miramar were equipped with AIM-9C by the fall of 1964.[2] Production of the missiles were carried out by Motorola.[3]

Usage

Though the AIM-9C was received by the US Navy, its more complicated seeker compared to the infrared seeker variant introduced technical issues. China Lake's development team, including Amlie himself, arrived at the Essex-class carriers to provide orientation and support for the missiles. The biggest issue aside from the missile was the Crusader's radar, which can fail and was difficult to repair. Pilot confidence in the missile was also poor, both in regards to the Crusader's radar reliability and the AIM-9C's ability for an all-aspect attack with the radar as they were used to the Sidewinders being a rear-aspect weapon.[4]

However the ultimate failing of the AIM-9C's is its purpose filling a niche role on an aircraft with a specific radar requirement, being meant for the Crusader because the aircraft could not carry the AIM-7 Sparrows. Once the Crusaders began being phased out in the mid-1960s, the AIM-9C was phased out alongside the Crusaders as newer aircraft like the F-4C Phantom II that can use Sparrows were put into use. With the AIM-9C only seeing brief service before its retirement with the Crusaders, only 1,000 AIM-9Cs were produced by Motorola between 1965 to 1967.[3] There were no kill claims during the Vietnam War credited to the AIM-9C.[5]

The AIM-9C would have another chance in the 1980s. Making use of the inventory of AIM-9Cs that have been phased out of use, the US Navy converted the AIM-9Cs into the AGM-122A SideARM ("Sidewinder Anti-Radiation Missile") for use against radar installations. In 1984, Motorola was contracted to perform the conversions, which utilized a wide-band passive electromagnetic radiation homing seeker, as well as a new proximity fuse and rocket motor used on the more modern AIM-9L Sidewinder. While not as useful as a dedicated anti-radiation missile, the AGM-122A provided a cost-effective solution against smaller radar threats. The primary users of the AGM-122A was the United States Marine Corps, who received 700 units between 1986 to 1990 and equipped on fixed wing aircraft such as the AV-8 Harriers and A-4 Skyhawks, as well as helicopters such as the AH-1 Cobra.[6][7][8] Once the AIM-9C inventory ran out, there were considerations to restart production for new missiles as the AGM-122B with new guidance system and a reprogrammable memory board, but this was cancelled.[6]

Media

- Videos

See also

- Related development

- Other SARH missiles with IR seeker alternatives

- R-3R (IR: R-3S)

- R-23R (IR: R-23T)

- R-24R (IR: R-24T)

- R-27R (IR: R-27T)

- R-27ER (IR: R-27ET)

- Matra R530 (IR: Matra R530E)

External links

References

- Citations

- Bibliography

- McCarthy, Donald J. Jr. MiG Killers, A Chronology of U.S. Air Victories in Vietnam 1965–1973. Specialty Press, 2009.

- Parsch, Andreas. "AGM-122." Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Designation-Systems.Net, 08 November 2002, Website. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2021 (Archive).

- Parsch, Andreas. "AIM-9." Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles, Designation-Systems.Net, 09 July 2008, Website. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2021 (Archive).

- Rogoway, Tyler. "The AGM-122 "Sidearm" Came To Be From A Novel Missile Recycling Scheme". The Drive, 29 Jun. 2017, Website. Accessed on 20 Nov. 2021 (Archive).

- Westrum, Ron. Sidewinder; Creative Missile Development at China Lake. Naval Institute Press, 30 Sep. 2013.